Salvage of the pathological proximal femur X-ref

There is a misconception among surgeons that pathological fractures of the proximal femur through a benign lesion necessitate replacement. Surgeons from Caracas (Venezuela) set out to dispel this myth with their own comparative series of patients treated for both proximal femoral fracture, and without a fracture through benign bone tumours.1 The authors report the outcomes of 97 patients treated overwhelmingly with fixation (86.2% for pathological fractures and 98.5% for those without fracture). Local recurrence risk was similar for patients in the pathological fracture (10.3%) and non-fractured groups (8.8%) with excellent functional outcome scores in both groups and not statistically significantly different. The authors concluded that the majority of pathologic fractures through a benign bone tumour of the proximal femur can be successfully treated with curettage, burring, bone grafting and internal fixation without increasing the risk of local recurrence or negatively impacting functional outcome when compared to those without a fracture.

Fractures in giant cell tumour of bone

There is ‘common sense’ presumption that pathological fracture can lead to localised spread, seeding and recurrence of benign tumours, and as such patients presenting with pathological fractures should perhaps be treated with a more aggressive approach than those with lesions that are not fractured. Researchers in Singapore (Singapore) have undertaken a meta-analysis to establish if this approach is evidence-based, using the giant cell tumour.2Their literature review and meta-analysis included the results of 19 papers reporting the outcomes of 3215 patients, all of whom had undergone treatment for giant cell tumour (GCT). The cohort included 580 patients who underwent treatment for fracture. There was no difference in local recurrence rates between patients who have a GCT of bone with and without a pathological fracture at the time of presentation, and neither was there a difference in outcomes between those patients undergoing curettage with and without a fracture. The resounding message from this paper is that based on the evidence currently available, there are no grounds for treating patients presenting with a GCT fracture any differently to those without.

Giant cell tumour in the distal radius X-ref

In a tour de force of current benign bone tumour research we would draw readers’ attention to a further paper concerning the giant cell tumour (GCT) from authors in Chicago (USA). The study team report their results of 39 patients treated for GCT of the distal radius over a 23-year period.3 Patients reported here were either treated with primary intralesional excision (n = 20), resection with wrist arthrodesis (n = 15) or resection with osteoarticular allograft (n = 4). It is difficult to draw conclusions from a small series with differing presentations and treatment strategies, making each group too small for subset analysis. What the authors are able to conclude, however, is that resection for giant cell tumour of the distal radius with an allograft arthrodesis showed a lower recurrence rate, lower re-operation rate, and no apparent differences in functional outcome compared with joint salvage with intralesional excision. The authors stop short of recommending resection for all cases and adopt the ‘middle path’, concluding that because arthrodesis after recurrence yields similar functional scores to the initial resection and arthrodesis group, an initial treatment with curettage remains the first line in uncomplicated GCT of the distal radius. However, fusion clearly yields excellent results, and here at 360 we would tend to agree with the authors that in those patients with joint involvement or extensive bone loss, a primary arthrodesis is an excellent option.

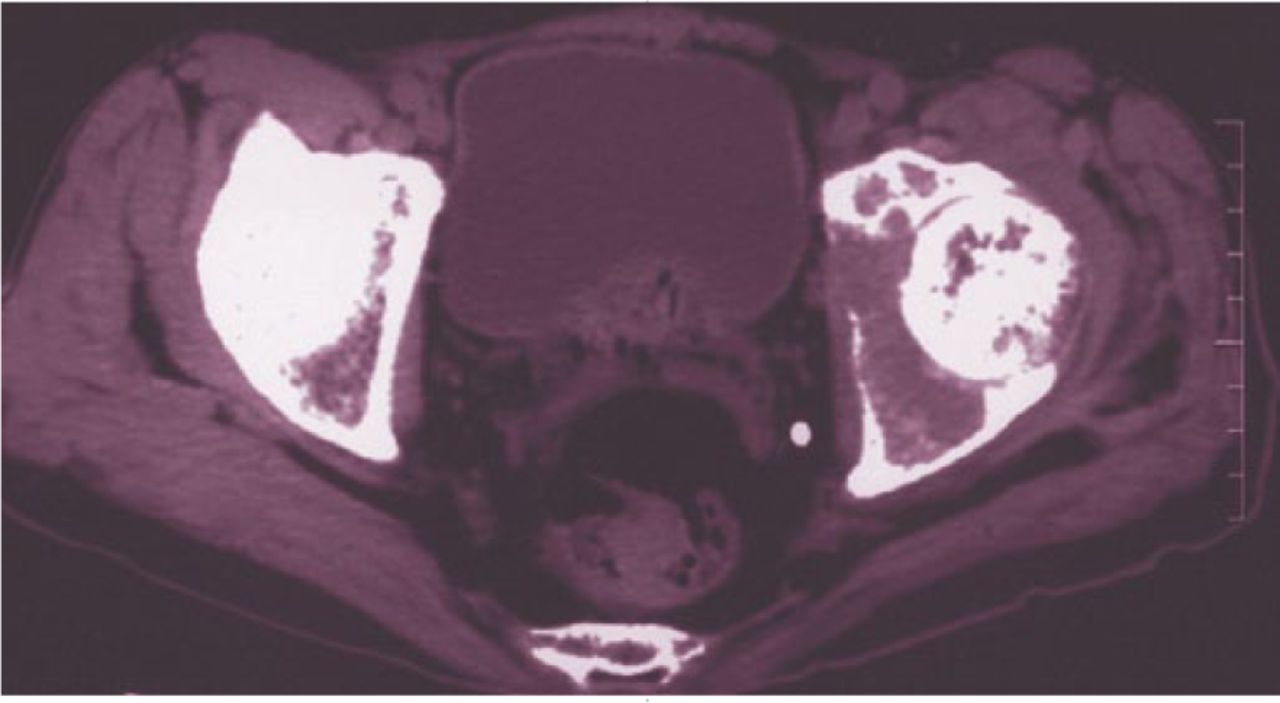

Fig.

Growing prostheses in children X-ref

Endoprosthetic replacement in children following resection of a malignant bone tumour is still a controversial intervention. Although the newer growing prostheses minimise the complexity of re-operations, these prostheses are still associated with a high number of re-operations and an uncertain longevity. Orthopaedic oncologists in Vienna (Austria) share their experience over 27 years of 71 patients treated with excision and growing prosthesis for extremity sarcoma.4 Of the initial 71 patients, 12 died from their disease and outcomes were excellent with an MSTS score of 87.8%. Despite the excellent functional results, patient averaged 2.5 operations for complications, of which the most common were soft-tissue-related (46%), structural failure (28%), infection (17%), and aseptic loosening (8%). This is a reliable and honest look at the longer-term outcomes of patients presenting with extremity sarcomas. The high number of complications should be offset against successful lengthening of an average of 70 mm and excellent long-term functional outcomes. Lengthening prostheses will always be a balance of risks and benefits, and this report provides excellent data on which to make this choice.

The unplanned sarcoma excision X-ref

There will always be an incidence of unplanned surgical excision of bone tumours. Seemingly benign lesions are excised successfully in small units throughout the world, however, every once in a while a poor work up, or simply surprising histology will lead to the referral to a regional bone tumour centre of a patient following a ‘whoops manoeuvre’. This poses a difficult situation for the receiving surgeon. Should they rely on the margins and histology from the primary surgery, or should patients routinely undergo further surgery? A team in Freiburg (Germany) undertook a review of all such patients over a ten-year period and compared them with those initially treated in their centre.5 In this series of 204 patients, over half (n = 110) were secondary referrals and 71 had undergone attempted excision without suspicion of malignancy. In these, there was a 53% residual tumour incidence, and the initial histopathology report was inaccurate in around half of cases. While clearly education and comprehensive tumour networks are essential to reduce the rates of such procedures, it is evident from this large series that receiving surgeons should have a low threshold for re-exploration and re-excision of patients’ tumours when there is any cause for doubt if the initial surgery has not occurred at a tumour centre.

Imaging and cartilage lesions

Grade one chondrosarcoma is a tricky diagnosis – both to be confident in making and confident in treating. However, unlike the truly benign encondroma, grade 1 chondrosarcoma is a malignant lesion and should be treated more aggressively. The difficulty, however, is in making the diagnosis. Researchers in Columbia (USA) have undertaken a diagnostic study to ascertain just how accurate modern imaging techniques are in making this subtle distinction.6 Their study reports the outcomes of 53 cases of enchondroma and grade 1 chondrosarcoma (all with a definitive histopathological diagnosis). The study team included two MSK radiologists who, after agreeing the criteria for malignancy, independently reported the contrast MRI scans and radiographs for all 53 cases. Perhaps surprisingly, the results were not as accurate as perhaps we might intuitively expect. The radiographs alone were actually misleading for chondrosarcoma with only 20% of cases correctly diagnosed (n = 5/24) and the MRI scans were only marginally better than a coin toss (58%; n = 14/24). This paper really does highlight the difficulties faced in making these diagnoses. While we are perhaps not surprised that diagnosis is difficult to reach on imaging alone, it does highlight to us the importance of thorough assessment and intervention when there is the suspicion of malignancy.

References

1. Carvallo PI , GriffinAM, FergusonPC, WunderJS. Salvage of the proximal femur following pathological fractures involving benign bone tumors. J Surg Oncol2015 (Epub ahead of print).CrossrefPubMed Google Scholar

2. Salunke AA , ChenY, ChenX, et al.. Does pathological fracture affect the rate of local recurrence in patients with a giant cell tumour of bone? A meta-analysis. Bone Joint J2015;97-B:1566-1571. Google Scholar

3. Wysocki RW , SoniE, VirkusWW, et al.. Is intralesional treatment of giant cell tumor of the distal radius comparable to resection with respect to local control and functional outcome?Clin Orthop Relat Res2015;473:706-715.CrossrefPubMed Google Scholar

4. Schinhan M , TiefenboeckT, FunovicsP, et al.. Extendible prostheses for children after resection of primary malignant bone tumor: twenty-seven years of experience. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]2015;97-A:1585-1591.CrossrefPubMed Google Scholar

5. Koulaxouzidis G , SchwarzkopfE, BannaschH, StarkGB. Is revisional surgery mandatory when an unexpected sarcoma diagnosis is made following primary surgery?World J Surg Oncol2015;13:306.CrossrefPubMed Google Scholar

6. Crim J , SchmidtR, LayfieldL, HanrahanC, ManasterBJ. Can imaging criteria distinguish enchondroma from grade 1 chondrosarcoma?Eur J Radiol2015;84:2222-2230.CrossrefPubMed Google Scholar