Abstract

While the demand for orthopaedic surgical expertise in the developing world is in critically short supply, short-term remedy from visiting doctors cannot solve this long-term healthcare problem. Capacity building by senior and training orthopaedic surgeons from established Western training programmes can offer a significant contribution to the orthopaedic patient in the developing world and the gains for those visiting are extremely valuable. We report on several visits by a UK orthopaedic team to a hospital in Kabul, Afghanistan and discuss the operative and non-operative case mix and the benefits in terms of local capacity building and the unique experience of those visiting.

“In memory of Dr Jerry Umanos who was tragically killed at Cure International Hospital, Kabul, in April 2014”

Introduction

The humanitarian side of relief work in less developed parts of the world are well documented and a number of high- and low-profile non-governmental organisations (NGOs) ranging from the Red Cross through to smaller relief charities are well described.1 Views, however, are somewhat mixed on the different models for care delivery. There is almost universal agreement that capacity building and teaching and training for sustainable local healthcare economy is more effective than simply service delivery.2 The benefits of overseas experience are not simply a one-way street, and in low to middle income countries the benefits of additional case mix exposure for surgical trainees are well documented.3 For some time general surgical and plastic surgery residency programmes in the United States have formally incorporated global health agendas into their training schemes largely in response to pressure from trainees.4,5 While placement of trainee surgeons in unfamiliar and often demanding environments with their inherent financial and cultural barriers can only be undertaken with considerable foresight, the potential benefits are immense.6-8

Partnership with developing world healthcare organisations can provide benefits for trainees, trainers, healthcare organisations and, most importantly, the population they intend to serve. When such collaboration is harnessed effectively it can drive forward capacity building in areas of need. The term ‘capacity building’ encompasses all that is necessary to bring individuals, institutions and communities together to develop the knowledge, skills, leadership and resources needed to address the needs of those they serve.9 It is not simply bricks and mortar, it is the glue that bonds and this is where trainees can help the most.

A contemporary example of effective capacity building involving UK trainees can be seen in the example of a series of six visits to the Cure International Hospital, Kabul. A consultant orthopaedic surgeon from the UK, through a series of visits, managed local patients and established relationships with the receiving organisation and local community. In the most recent visit two senior UK orthopaedic trainees accompanied and contributed to patient care while training local residents and establishing a sustainable relationship. We present data from the trip and discuss the difficulties and accomplishments faced, including the patient demographic and pathology type seen and procedure types performed.

Kabul, Afghanistan and Cure International Hospital

Afghanistan is a country of contrasts, set high in the mountainous belt between Asia and the Middle East, bordering Iran in the west and Pakistan and China in the east. The geographical contrasts, from the majestic Karakorum range in the north to the fertile poppy fields and desert in the south, are matched only by the contrasting social, tribal and religious divides within the country.

The people of Afghanistan have experienced continual war, civil or otherwise, since 1973. The Taliban movement rose out of discontent with the poor security situation and ongoing conflict. The corruption widely recognised as rife within the high command of the governing Mujahideen gave ample platform for the hard line Islamist Taliban, a loosely organised Islamic group preaching a very strict reserved brand of Islam. Under the ten years of Taliban control, books and music were illegal and strict punishments for breaking Sharia law were commonplace. While male doctors, teachers and nurses were still trained they had no study materials, leading to an education vacuum. Most of Kabul is without running water or closed sewer systems. Whilst efforts have been made to bring mains electricity supplies to most of the city, power cuts are commonplace and many communities within Kabul still rely on generated power. The majority of Afghans depend on hand-operated pumps to obtain water and walk several miles to reach them.

Health care in Afghanistan is provided by four main providers, Government Hospitals, NGOs, Private Healthcare and Allied Military Services.While Government Hospitals provide free health care to the population, their resources are extremely limited with 14 consultant orthopaedic and trauma surgeons serving a country of 42 million. The NGOs provide ‘subsidised’ health care where patients pay a fee at the point of service provision and can purchase outpatient medicines while all surgical implants and other items used in their care are provided free of charge. Cure International Hospital Kabul is an NGO established in 2005 and is part of a not-for-profit American hospital group. The hospital is located in the outskirts of Kabul and runs a three-year family practice training programme teaching doctors significant general medicine, general surgery, obstetrics and paediatrics. They have intermittent exposure to orthopaedics, anaesthesia and neurosurgery but no formal training in orthopaedic or trauma surgery is provided.

Methods

During six visits to the Cure International Hospital Kabul (CIHK), between October 2009 and June 2011, a patient consultation and operative log was maintained including patient demographics, presenting pathology type and subsequent management. Cure International, an NGO, established this hospital in 2005 and has consistently developed postgraduate training in general surgery, obstetrics and gynaecology, as well as family health scheme but has not yet formalised an orthopaedic service or training programme. Careful pre-trip planning yielded a comprehensive programme aimed at capacity building. Using links forged during previous visits, the presence of orthopaedic specialist surgeons was publicised to surrounding clinics and throughout Kabul itself. We organised a comprehensive programme of clinic, bedside and operating theatre teaching with the local family health (general practice) residents with the aim of providing hands-on clinical experience combined with lunchtime lectures and grand round teaching. We also sought to demonstrate the significant burden of local orthopaedic pathology to the management of CIHK with the aim of establishing a formal local orthopaedic presence at the hospital. Capacity building, however, is not based around a single institution and any meaningful change must sit well within the local healthcare economy and to that end we met with the medical director at the Wazir Ikbar Kahn Government Hospital to engage with their orthopaedic trainees.

Results

Over 800 outpatient consultations were carried out with outpatient procedures performed and taught to local trainees where the most productive visit was the latter with support from two orthopaedic registrars. The clinic setting was both the ‘family health’ clinic and some private consultations (the fees from which were donated to support the care of the less wealthy).

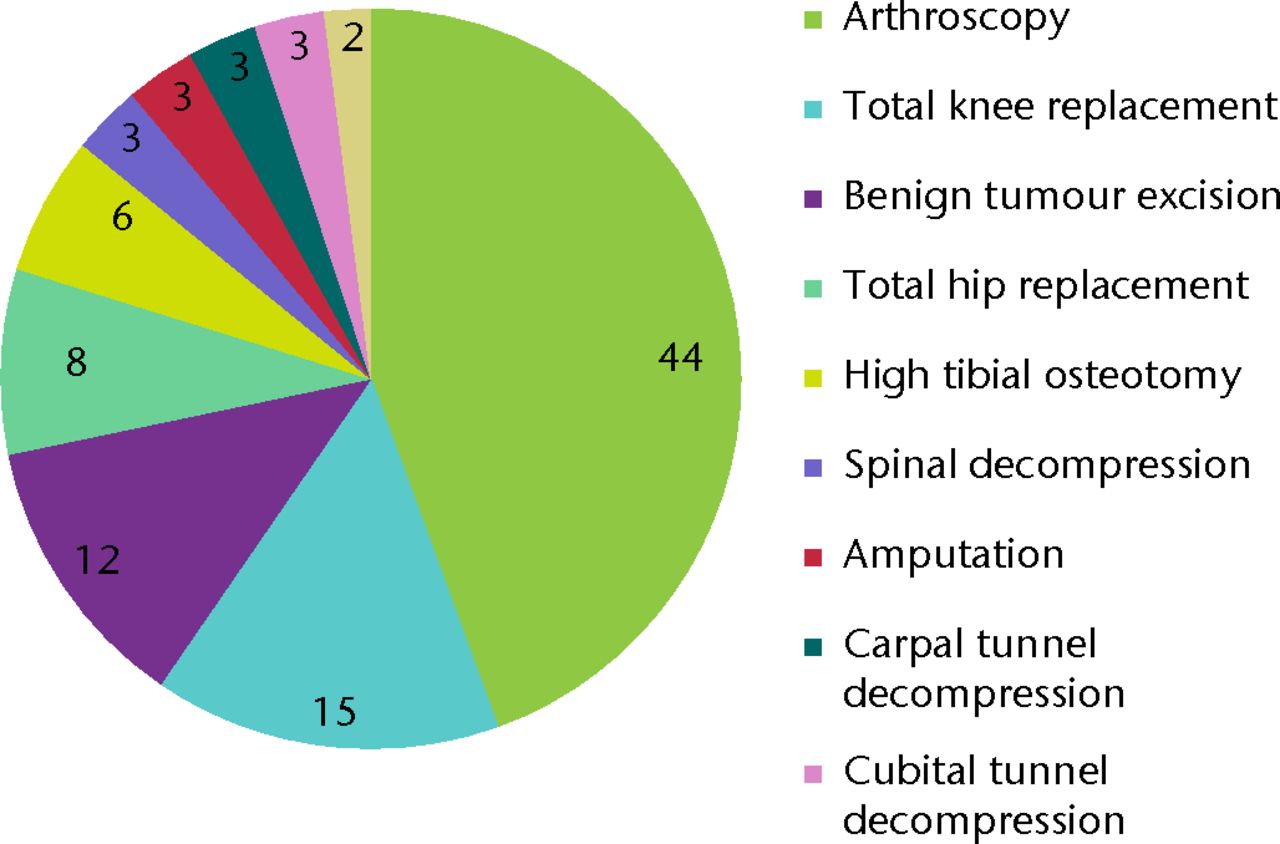

Over the course of six trips, 68 surgical procedures were performed for a variety of conditions ranging from degenerative musculoskeletal disease (such as knee osteoarthritis) to neglected limb trauma and children’s orthopaedics with a particular burden of developmental hip dysplasia, talipes equino varus and cerebral palsy.

Orthopaedic infections were surgically managed including sequestrectomy for established localised chronic osteomyelitis in addition to deformity correction (upper limb gunstock deformity, lower limb Blounts disease) undertaken by the senior clinician assisted by trainees in every case, providing a whistlestop tour of advanced debilitating conditions and surgical remedy in a short period of time.

The diverse array of orthopaedic conditions encountered both in the clinical and operative setting provided a high concentration of teaching and knowledge exchange, with the Afghan doctors benefiting from a comprehensive education on common musculoskeletal conditions including learning how to inject joints, recognise septic arthritis and aspirate joints, as well as education surrounding commonly encountered paediatric conditions. The UK trainees benefited from the high concentration of rare orthopaedic complications and the experience of working in an unusual and sometimes difficult environment.

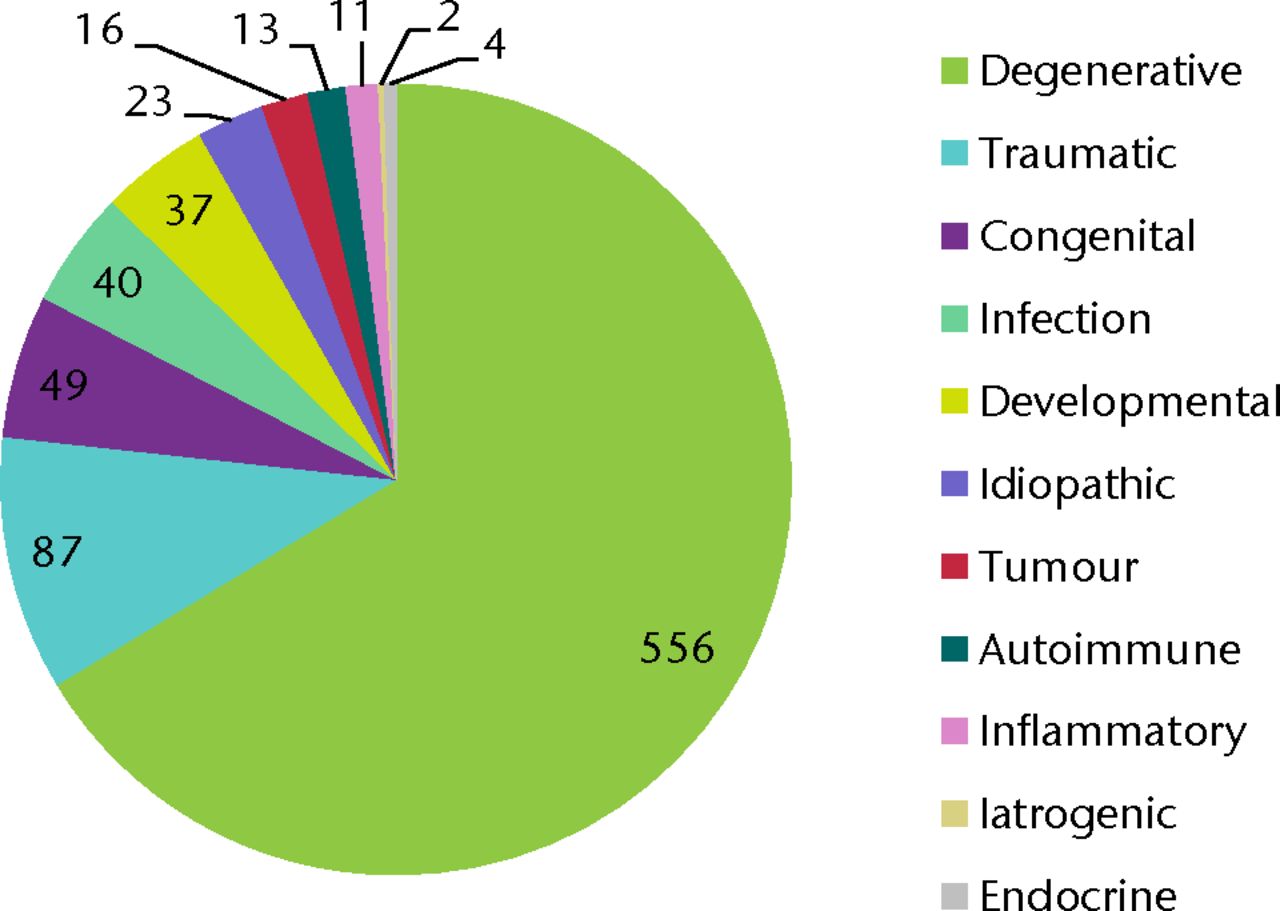

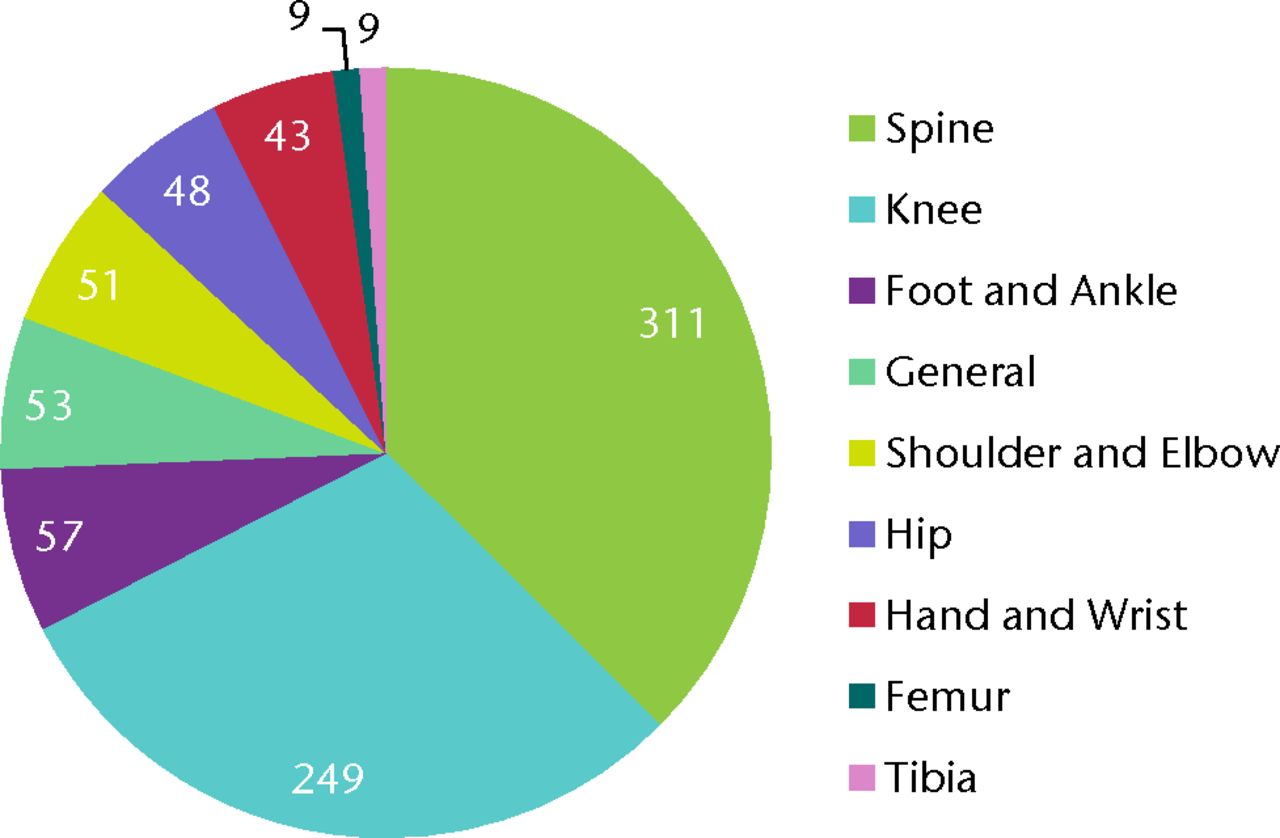

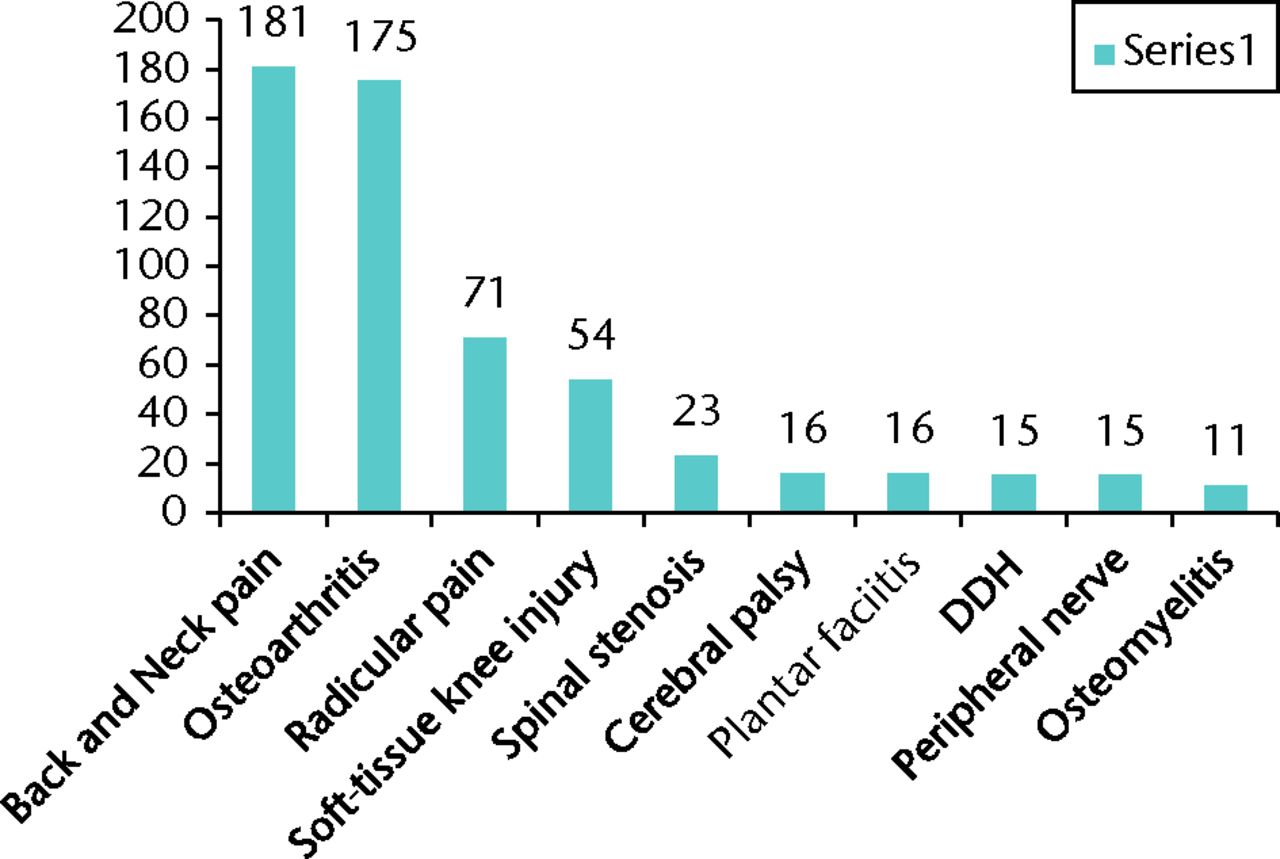

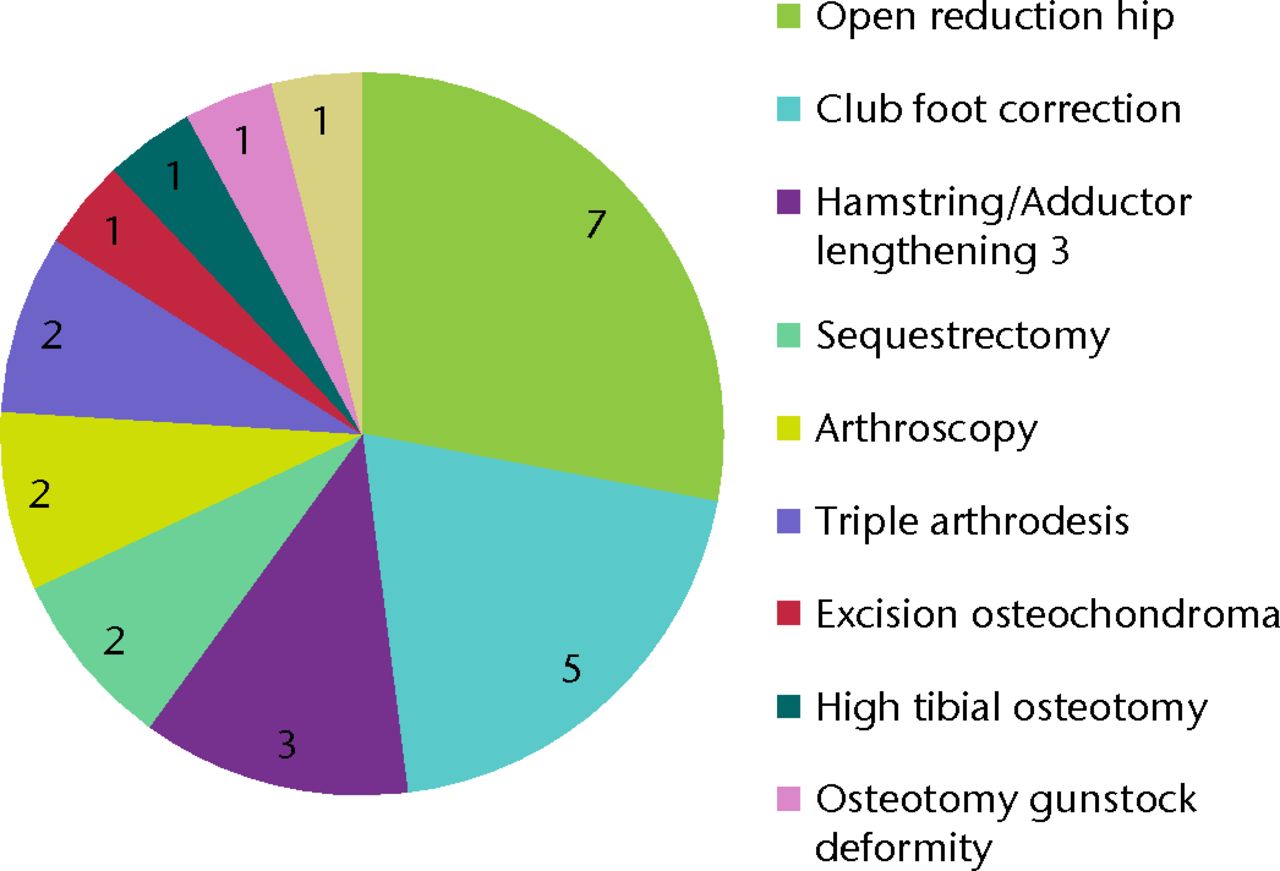

Table I and Figures 1 to 3 illustrate the range of orthopaedic conditions encountered in adult and paediatric age groups while Figures 4 and 5 show the procedures performed.

Table I. Patient demographics and number of procedures performed (adult and paediatric)

| Age (yrs) < 16 | 68 |

| > 16 | 774 |

| Male:Female | 44:56 |

| Outpatient procedures | 116 |

| Outpatient consultations | 843 |

| Inpatient procedures | 68 |

Fig. 1

Pathology type

Fig. 2

Body region affected

Fig. 3

Most most common diagnoses

Fig. 4

Procedures (adult)

Fig. 5

Procedures (children)

Discussion

An outstanding number of western practicing and retired orthopaedic surgeons regularly visit overseas orthopaedic departments in low or middle income countries providing their time and expertise.10 They do not typically, invite trainees to accompany them on these trips, possibly due not only to concern for the trainees’ safety but viewing such an exposure as inappropriate for those still taking their first surgical steps. There is a long history of senior trainees providing supervised and unsupervised care in their own communities, and often ‘trainees’ have much to offer, particularly with teaching networking and helping to provide a more comprehensive team-based approach than a single consultant surgeon could.11 Our experience in Afghanistan, supported by numerous accounts from trainees in other disciplines, outlines the many benefits of such a supervised experience, both short- and longer-term, to the trainee as they move forward and become consultants, notwithstanding what they and their residency programme can contribute to the receiving hospital.11,12

While these trips provided much needed orthopaedic input to a small number of Afghan patients’ the aim of such efforts is not to treat a deserving few, but to build, from the ground up, a greater local capacity to deliver care that is self-perpetuating and ongoing once the visiting team leaves. There is a danger, however, that such trips may be seen as a chance for inexperienced, over-confident surgeons to wade in and manage complex surgical conditions that they would not be treating at home, or to carry out difficult operations only then to hand over ongoing care to inexperienced local practitioners. The involvement of local healthcare providers and experienced developing world surgeons is essential to ensure that input is as effective as possible. Sometimes the most well-meaning ‘help’ can, in the worst case, be harmful.13

The aim during the visits to Kabul was to ascertain if a series of visits by Western teams could contribute to local orthopaedic capacity building and leave an ongoing legacy reaching a critical mass of trained family doctors and surgeons in Afghanistan over time through a multiplier effect. While we did gain direct exposure to advanced and rare pathology, that was not the point of the trip, merely a bonus. More importantly, we taught five local residents the basic management principles of common orthopaedic complaints, supervised their teaching over a period of time in the outpatient setting and we successfully made the case with CIHK management for a part-time orthopaedic presence at the hospital. Engaging with the wider local community was also surprisingly effective. Through understanding and communication we gained the permission of the local Government Hospital to formally engage with their orthopaedic residents. Where criticism can sometimes be easy (we were all shocked to see the two patients in the same operating theatre with surgeons sharing instruments between patients) support and engagement in development can be more difficult. In a country with as many complex needs as Afghanistan the most important changes are often the simplest and start with understanding. Engagement of local trainees with more comprehensive healthcare models could be the most important part of the visit and encompasses the essence of capacity building at the community and organisational level. With a better understanding of basic orthopaedic principles, infection control techniques and management fundamentals, this centre could vastly alter the course of a large number of orthopaedic conditions for local people, and within the wider Afghan community at the very least.

Caution is naturally advised when embarking on an overseas trip such as this and ethical considerations are as important there as they are at home. Firstly, to take trainees into an environment such as Afghanistan without attaining an appropriate level of competence and pre-trip orientation would be irresponsible. In addition, costs must be absorbed by the trainees and are unlikely to be supported by training programmes. Finally, it is vital that trainees adapt to the environment in which they are working and follow not only cultural but financial etiquette, respecting the limited resources available and working within, not stretching, those boundaries.13,14

We would propose that the benefits to trainees of working in challenging environments, negotiating cultural obstacles, working within budget constraints, teaching and training others and observing the management of complex, advanced, late presenting conditions is not dissimilar to learning objectives on home soil. While consultant surgeons are fundamental to the surgical management of complex conditions whatever the environment or location, out of the operating theatre trainees can add value in other ways, building capacity through cultural understanding, engaging with their training counterparts and promoting greater collaboration between local training doctors and their surrounding communities. For orthopaedic trainees, this brief exposure to developing world orthopaedics stands apart as a very memorable and valuable component of orthopaedic training. However, more than the nuts and bolts of the orthopaedic experience, it is the humanitarian aspect of this work that shines most brightly by being in the privileged position of being able to not only directly help patients with neglected, painful and disabling conditions but at the same time contribute to the training of native doctors. To experience medicine in this environment makes you remember why you trained as a doctor, before the realities of the working time directive, medical litigation, four hour waits and 18-week pathways became a constant feature of hospital medicine and when all that mattered was helping the patient in front of you. On returning to the UK after a dangerous trip with arduous hours it is difficult not to approach medicine feeling completely refreshed.

1 Coughlin RR , KellyNA, BerryW. Nongovernmental organizations in musculoskeletal care: Orthopaedics Overseas. Clin Orthop Relat Res2008;466:2438–2442.CrossrefPubMed Google Scholar

2 Casey KM . The global impact of surgical volunteerism. Surg Clin North Am2007;87:949–960.CrossrefPubMed Google Scholar

3 Hill AG , WoodfieldJC. Training outside of the box. ANZ J Surg2003;73:881–883.CrossrefPubMed Google Scholar

4 Ozgediz D , RoayaieK, DebasH, SchecterW, FarmerD. Surgery in developing countries: essential training in residency. Arch Surg2005;140:795–800.CrossrefPubMed Google Scholar

5 Ozgediz D , WangJ, JayaramanS, et al.Surgical training and global health: initial results of a 5-year partnership with a surgical training program in a low-income country. Arch Surg2008;143:860–865.CrossrefPubMed Google Scholar

6 Coughlin R . Overseas volunteering: the antidote to managed care. Hospital Physician2000;6:67–70. Google Scholar

7 Dormans JP . Orthopaedic surgery in the developing world: can orthopaedic residents help?J Bone Joint Surg [Am]2002;84-A:1086–1094. Google Scholar

8 Drain PK , HolmesKK, SkeffKM, HallTL, GardnerP. Global health training and international clinical rotations during residency: current status, needs, and opportunities. Acad Med2009;84:320–325.CrossrefPubMed Google Scholar

9 Zirkle LG . Injuries in developing countries: how can we help? The role of orthopaedic surgeons. Clin Orthop Relat Res2008;466:2443–2450. Google Scholar

10 McGinigle KL , MilanoPM, RichPB, VieraAJ. Volunteerism among surgeons: an exploration of attitudes and barriers. Am J Surg2008;196:300–304.CrossrefPubMed Google Scholar

11 Lavy CB , MkandawireN, HarrisonWJ. Orthopaedic training in developing countries. J Bone Joint Surg [Br]2005;87-B:10–11.PubMed Google Scholar

12 Campbell A , ShermanR, MageeWP. The role of humanitarian missions in modern surgical training. Plast Reconstr Surg2010;126:295–302.CrossrefPubMed Google Scholar

13 Crump JA , SugarmanJ. Ethical considerations for short-term experiences by trainees in global health. JAMA2008;300:1456–1458.CrossrefPubMed Google Scholar

14 Ramsey KM , WeijerC. Ethics of surgical training in developing countries. World J Surg2007;31:2067–2069.CrossrefPubMed Google Scholar