Abstract

Richard Carey Smith is an orthopaedic oncology surgeon with fellowship training in the UK, USA, Australia and Canada, and has worked in Zambia, Zimbabwe and Papa New Guinea. David Wood is head of the University Department of Orthopaedics in Perth, Western Australia. He did his masters in Africa, and first experienced Papa New Guinea on his medical elective, starting a lifelong commitment to medical aid work there.

Medical aid work: what are you waiting for?

Clinic

Papua New Guinea (PNG), Monday morning, 9.30 a.m.; it is hot, 35°C, maybe more and humidity is high. The clinic, in Lae Hospital (Fig. 1), is running fast with 150 patients waiting. Already we have booked six femoral nonunions for surgery. The most recent stands out. A 37-year-old man and sole carer for his six children, their mother having died four months earlier of cervical cancer. He is a bus driver, who fractured his femur nine months previously when the bus rolled as it turned, also killing six passengers. The man has been unable to work since and has been cared for in hospital by the extended family that sleep under his bed on the ward. The quality of the radiograph (Fig. 2) is poor but we feel the fracture can be intramedullary nailed - if nails were available. Yet the bus driver is the seventh nonunion and there are only six nails. It is first-come, first-served, so we opt for a compression plate instead. The patient enthusiastically agrees, uses a thumbprint to sign his consent and we move to the next patient.

Fig. 1

Photograph of ward at Lae Hospital, Lae, which is under resourced and in need of repair.

Fig. 2

A poor quality radiograph demonstrating a nine-month-old femoral nonunion.

This time it is a child, a seven-year-old girl with overgrowth of her first and second toes. Her toes are so large (Fig. 3) that the second toe drags on the floor and she has problems with footwear. She is requesting amputation of the second toe. We add the girl to an operating list for surgery later in the week.

Fig. 3

Photograph showing the overgrowth of first and second toes in a seven-year-old girl.

The word is out that we are here. Many patients have walked or been carried for long distances and some have been sent from a neighbouring hospital. There is a large collection of acute or neglected trauma, infected cases, and the results of local violence in a population for whom bows and arrows are still widely available, and used (Fig. 4).

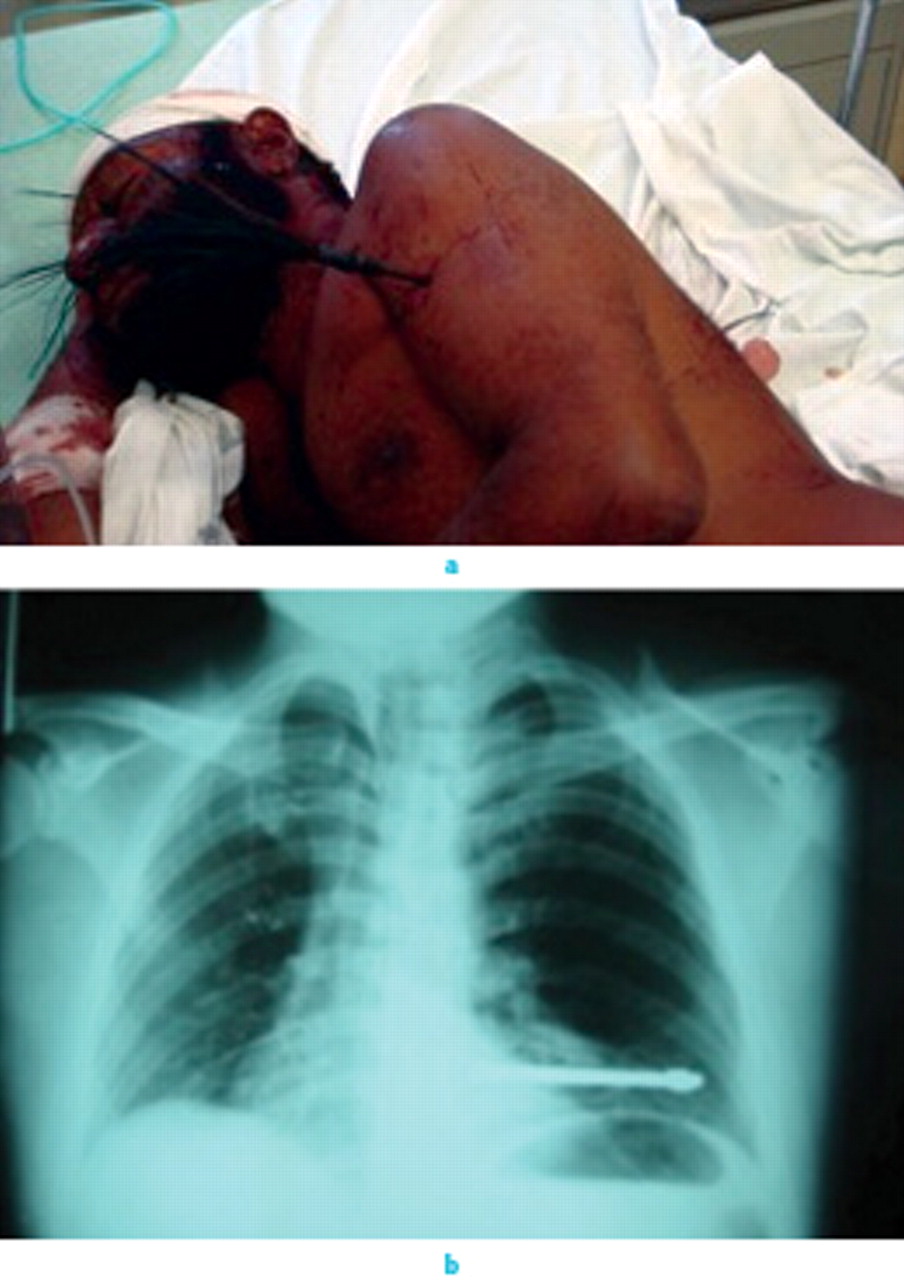

Fig. 4

Clinical photograph (a) and radiograph (b) of a penetrating arrow injury from village in-fighting (note arrows front and back).

The differences between a well-resourced university teaching hospital in the developed world and PNG are huge. PNG has an underfunded health service, few trained doctors and even fewer orthopaedic specialists (approximately ten in a population of 6.5 million), transport networks are underfunded, many jobs involve primitive machinery with limited safeguards, drink driving on poorly constructed roads is rife and domestic violence is high. Meanwhile, the mean annual income is AU$1040 and many people still live in traditional villages with 39% living below the poverty line.

Operating

Theatre starts early and our team, comprising a surgeon, anaesthetist and scrub nurse arrives at 7 a.m. to co-ordinate the operating list with the local nurses. With aid work preparation is key to success. Although most hospitals in PNG have basic fracture instrumentation sets, these may be incomplete. We have thus brought decommissioned but fully functional sets, as well as large and small plates, screws and intramedullary devices. We have also brought power tools and ensure that our planning leaves time for these to be re-sterilised between cases. An ability to improvise is key, so we have on occasion used a domestic, do-it-yourself drill in a bag with sterilised drill bits, in order to treat osteomyelitis. We also keep a torch handy during surgery so that operations can be completed in the event of a power cut.

Although gloves and masks are available we bring plenty of both, as well as disposable gowns. Local gowns are used until threadbare, then repaired and used some more. Meanwhile local gloves are recycled.

The checks are done and we are ready to start. Regional anaesthesia works well with limited resources. The teaching of common nerve blocks has brought effective analgesia to many patients as local staff have become experts. Nerve blocks also offer good post-operative analgesia.

Another key item, but with limited availability, is blood. Open reduction of established malunions, or amputations for tumours, are challenging for both surgeon and anaesthetist. The wantok system, where one relative is obligated to help another, is widespread in PNG. This encourages blood donation within families and appropriate access to blood products.

Education

Education is a key component of all visits on behalf of the Royal Australasian College of Surgeons and AusAID.1 It can be wide ranging, so we run courses on the principles of trauma, and we teach on ward rounds, in clinics, and in the operating theatre. Educational meetings are held over the lunch break, which are well attended, and specific educational days, usually at least once a week, are held at hospitals and in local schools.

Safety

Safety of team members is essential and remains a major concern. It impacts upon productivity by limiting the duration of afternoon lists, as all staff must leave by sunset. Poverty has led to an escalation of violence, and roads that are difficult by day may become lethal at night. So, once we have finished the post-operative ward round and prepared our equipment for the next day, we leave, ready to return the following morning.

Why go?

Medical aid work is demanding yet rewarding and there is a definite need. Not all aid work is beneficial, however well-meaning it may be,2 and the principle of primum non nocere is key. For us, perhaps the biggest reward is to know that we are making a genuine difference to people’s lives, and the smiles say it all (Fig. 5). It is then that we know our efforts have been worthwhile.

Fig. 5

Photograph of the big thank-you which makes it all worthwhile.

1 No authors listed. Royal Australian College of Surgeons: International Development Program: Papua New Guinea. http://www.surgeons.org/racs/external-affairs/international-development-program/papua-new-guinea (date last accessed 4 January 2011). Google Scholar

2 Bishop R , LitchJA. Medical tourism can do harm. BMJ2000;320:1017.CrossrefPubMed Google Scholar